-

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF DEMINERALISED FREEZE-DRIED BONE (DFDBA), FRESH FROZEN BONE ALLOGRAFT (FFBA) AND AUTOGENOUS BONE GRAFT (AU)—A HISTOLOGIC STUDY IN RABBITS

Objectives: There are different clinical applications for bone grafts in alveolar reconstructions and difficulties in achieving vertical osseous increase. This study was to make a comparative histological evaluation of DFDBA, FFBA, AU and blood clot (CO) on vertical guided bone regeneration (GBR) in rabbit calvaria. Methods: Nine rabbits were used. One was the primary bone graft donor and eight were GBR models, whereby 32 titanium cylinders were fixed to the calvaria and randomly filled with DFDBA, FFBA, AU or CO. The animals were killed 13 weeks later and the contents of the cylinders were analysed histomorphologically and histomorphometrically to quantify the total area (AT) of newly formed tissue, new bone (NB) and residual graft (RG) particles. Results: Mean values of AT were significantly higher for DFDBA and FFBA in the order DFDBA = FFBA > AU > CO. New bone formation with DFDBA and FFBA was better than with AU or CO. There were more RG particles in the DFDBA models, in the order FFBA > DFDBA = AU = CO (p values Conclusions: Allografts containing DFDBA and FFBA can be considered beneficial for achieving new vertical bone formation. -

BIO-ACTIVATION OF DEPROTEINISED BOVINE BONE MINERAL (DBBM) AND NON-CROSS-LINK COLLAGEN MEMBRANES BY THE USE OF GROWTH FACTORS EXTRACTED FROM FRESH AUTOGENOUS BONE CHIPS

Objectives: Autogenous bone grafts are the gold standard for bone augmentation procedures with the ability to release growth factors. These growth factors can be isolated into a "bone-conditioned medium" (BCM). No effort has been made to utilise the growth factors from fresh bone chips in combination with biomaterials to improve bone regeneration. This study aimed to investigate the ability of collagen barrier membranes and DBBM treated with BCM to affect cell behaviour. Methods: Cortical bone chips were harvested from fresh pig mandibles with a bone scraper and placed into plastic dishes containing serum-free culture medium (5g of bone chips per 10mL of medium) for 24 hours. Natural collagen membranes (Bio-GideTM/®) were incubated with BCM for various times. Membranes were also (i) incubated for 4 hours with recombinant TGF-β1; (ii) exposed to ultraviolet light prior to BCM incubation; (iii) pre-wetted for 15 minutes with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) prior to BCM incubation; or (iv) dried and stored at room temperature for 7 days after BCM incubation. After incubation, the membranes were vigorously washed with PBS. DBBM particles (Bio-OssTM/®) were coated with BCM for 5 minutes prior to cell seeding. Gingival fibroblasts or bone-marrow-derived stromal cells (ST2 cells) were seeded on the collagen membranes and DBBM particles, respectively. Messenger RNA levels of BCM target genes were analysed by qRT-PCR using adrenomedullin (ADM), pentraxin 3 (PTX-3), interleukin 11 (IL-11) and proteoglycan-4 (PRG-4). The morphology and viability of cells seeded onto collagen membranes was evaluated. Further, DBBM with and without a BCM coating was compared in terms of cell recruitment, adhesion, proliferation and qRT-PCR for osteoblast differentiation markers (including Runx2, COL1A2, ALP and OCNAlizarin red stain was used to assess mineralisation. The student‘s t-test was used for analysis. Results: Incubation of collagen membranes with BCM for at least 1 minute reduced fibroblast ADM and PTX-3 expression, and increased IL-11 and PRG-4 expression. The four different membrane treatments (i–iv) also provoked significant changes in gene expression. Likewise, conditioned medium from demineralised bone chips caused similar changes in gene expression compared to BCM. BCM did not alter the viability or morphology of gingival fibroblasts on collagen membranes. Coating BCM on DBBM particles improved cell migration of ST2 cells and led toa two-fold increase in cell adhesion. No significant increase in cell proliferation was observed, but BCM significantly increased mRNA levels of COL1a2, ALP and OCN at 3 days post-seeding. A three-fold increase in alizarin red staining was observed on DBBM particles that were pre-coated with BCM. Conclusions: Collagen membranes rapidly adsorb the TGF-β activity of bone chips, and pre-coating DBBM with BCM enhances the osteoconductive properties of DBBM by mediating osteoblast recruitment, attachment and differentiation towards an osteoblast phenotype. These cellular effects of BCM, in combination with biomaterials, might contribute to the overall process of guided bone regeneration. Further animal studies are needed to characterise the added benefit of BCM as an autogenous growth factor for combination therapies. -

THE ROLE OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH IN A CASE OF LANGERHANS CELL HISTIOCYTOSIS WITH INITIAL PERIODONTAL MANIFESTATIONS

Objectives: The present case epitomizes the clinical situation of a single-system Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) mimicking aggressive periodontitis in a patient with no other clinical signs. Although this is a single observation, we highlight the importance of using a multidisciplinary approach in rare conditions like this for optimizing patient management. Methods: A 32-year-old Caucasian woman visited a private dental practice in Brescia, Italy, complaining of sensitivity in her mandibular left first molar. Clinical and radiographic examinations revealed recession, furcation involvement, mobility and severe alveolar bone loss, leading to a diagnosis of localised aggressive periodontitis. Over the next 3 years, the patient received non-surgical periodontal treatment, but failed attend successive follow-up appointments for undisclosed reasons. Her periodontal condition continued to worsen and multiple tooth extractions were carried out due to progressive periodontal destruction with impaired healing and development of ulcerative lesions. Panoramic radiographs were taken, and revealed severe alveolar bone destruction with “floating teeth” appearance, and an osteolytic bone lesion at the left angle of the mandible. With an overall clinical deterioration, and the possibility of an underlying malignant condition, the patient was referred for deep analysis. Results: No abnormalities were detected in laboratory and biochemical tests. Skull and sinus radiography revealed a 5-mm oval radiolucency at the left angle of the mandible. Then a radiograph of the lower leg revealed multiple osteolytic bone lesions of the left tibia. Bone-marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed to determine the nature of these lesions. Histopathology revealed a dense nodular proliferation of CD1a-positive and S100-positive Langerhans cells within bone, on a background of lymphocytic and granulocytic cells, consistent with LCH. An additional biopsy of the intra-oral lesion showed mature, disease-free, compact bone. However, a bone biopsy may be not representative of the entire structure, particularly in cases of intraoral localisation of LCH. Bidirectional Sanger sequencing analysis and pyrosequencing of DNA extracted from bone tissue of the tibia detected the presence of the BRAF-V600E hotspot somatic mutation, confirming a clonal origin of the neoplastic cells. Multidisciplinary investigations showed that the periodontal involvement was a manifestation of an underlying systemic disease (multifocal single-system LCH). The patient was then started on radiotherapy and but improvement of her oral and periodontal condition is yet to be confirmed. Conclusions: In the present case, LCH was unrecognised for several years. The periodontal disease progressed rapidly, leading to loss of most of the dentition, with persistent delays in soft tissues healing after extraction. Close monitoring of the oral signs may have allowed earlier diagnosis of LCH and prevent such rapid deterioration, possibly resulting in a better endpoint. Dentists and periodontists should be aware that rare systemic diseases such as LCH can produce oral manifestations as the first clinical sign. Such patients benefit from a multidisciplinary approach to identify and manage such entities. -

A REVIEW OF BISPHOSPHONATES—POSSIBLE MODES OF ACTION, ALTERNATIVE DRUGS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR DENTAL IMPLANT TREATMENT

Objectives: The review aimed to explore the pharmacophysiological modes of action of both oral and intravenous bisphosphonates and the potential for adverse events in patients receiving dental implant treatment. It aimed to gather evidence on the use of alternative drugs to bisphosphonates, as well as current recommendations and guidelines for dental implant therapy in patients receiving bisphosphonates. It was hoped to devise a clinical protocol for the management of bisphosphonate-treated patients. Methods: A Medline search was conducted to identify articles from the medical and dental literature between 1950 and 31 December 2014 according to well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Searches were made of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Embase for English-language studies published between 2000 and 31 December 2014. All cited references in the identified papers were cross-checked to ensure that no articles were missed. Given the rarity of studies with a sufficiently large prospective sample to determine the rate of failure (often over 10,000 patients are needed to achieve statistical significance), the heterogeneous studies yielded in this search (in terms of both design and outcome measures) were only suitable for descriptive analysis, rather than a meta-analysis. Results: The initial search of Medline and Embase yielded a total of 37 articles on bisphosphonates and dental implants. On further investigation, only 27 met the study inclusion criteria. There were eight retrospective studies and two case series evaluating the success rate of dental implants in patients with a history of bisphosphonate use, and another 17 articles consisting of case series and case reports. They described incidences of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in dental implant patients. In addition, two relevant articles from the Cochrane Library addressed interventions for treating osteonecrosis of the jaw bone associated with bisphosphonates. A second search of Medline and Embase for “bisphosphonates” (MeSH term) in conjunction with “oral soft tissues”, “oral hard tissues”, “avascular necrosis”, “jaw bone” and “modes/mechanisms of action” yielded a total of 51 English-language studies in humans. Late implant failures are reported in patients treated with oral bisphosphonates for more than 3 years, especially if they have existing integrated implants. Early failures are reported in patients treated with bisphosphonates before or at the time of implant placement. Most organisations agree that a safe approach is the best policy for dealing with patients on oral bisphosphonatess, by assessing the risks on an individual basis and obtaining appropriate consent. This requires close communication with the prescribing physician before surgical intervention. Several alternative drugs are available and their risks profiles also need to be determined in this context. Conclusion: Although many of the studies identified here have shortcomings, there does appear to be some risk associated with both implant placement and maintenance of osseointegrated implants in patients who take oral bisphosphonates. -

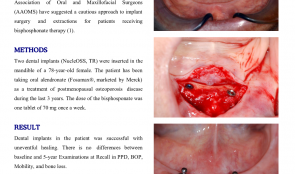

Clinical and radiografic evaluation with 5 years follow-up of two dental implant-supported mandibular overdentures in the patient receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy

Objectives: Systemic diseases may affect oral tissues by increasing their susceptibility to other diseases or by interfering with healing. Oral bisphosphonates (BP) are commonly prescribed for patients with osteoporosis to arrest bone loss and preserve bone density. The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) have suggested a cautious approach to implant surgery and extractions for patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. Methods: Two dental implants (NucleOSS, TR) were inserted in the mandible of a 78-year-old female. The patient has been taking oral alendronate (Fosamax®, marketed by Merck) as a treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis disease, during the last 3 years. The dose of the bisphosphonate was one tablet of 70 mg once a week. Results: Dental implants in the patient was successful with uneventful healing. There is was no differences between baseline and 5-year Examinations at Recall in PPD, BOP, Mobility, and bone loss. Conclusion: History of oral BP use is not an absolute contraindication for dental implant placement and dental implants can be osseointegrated successfully in this patient population. Great attention should be paid to the regular dental recall for implant-prosthetic restorations. -

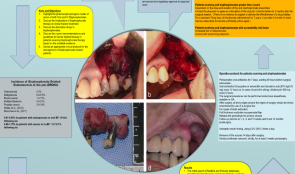

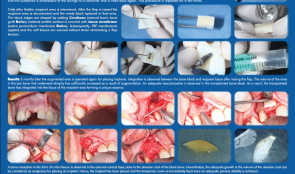

ACHIEVING A MORE EFFICIENT CONTACT SURFACE BETWEEN A BLOCK BONE AND RECIPIENT AREA USING A 3D STEREOLITHOGRAPHY (SLA) MODEL OF A JAW FRAGMENT IN ADJUSTING A HUMAN BONE BLOCK TO THE RESIPIENT AREA AND TIME SAVING DURING OPERATION

Objectives: Autogenic and allogenic bone block materials of different companies are increasingly used in guided bone regeneration (GBR) procedures. Adjusting block-shaped allogenic transplants to fit the recipient area is time consuming and technically challenging. A method of bone block formation using a 3-D stereolithography (SLA) model is reported here. Methods: A tomographic image of the area for augmentation was obtained and edited using Implant Assistant. Data from the image of the prepared 3-D jaw model were transferred to a 3-D printer (Objet Stratasys to produce a model of the jaw fragment. Unicortical cancellous block (Maxgrapht cortico-spongiosa) was moulded onto the model and holes for fixation screws were drilled into the material. The bone block was added to a 100-grams syringe filled with serum, emptied out in to a container and refilled. This procedure was repeated several times. After raising a flap, the recipient area was decorticated and the prepared block put in place. The edges were shaped by adding natural bovine bone graft (Cerobone) material and the surface was covered with native pericardium membrane (Jason membrane). A platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) membrane was then applied and the soft tissues sutured without strain to avoid flap tension. Results: After 6 months, the augmented area was re-operated for implant placement. Integration was observed between the bone block and recipient tissue after raising the flap. The volume of jaw atrophied bone had increased as a result of augmentation. There was adequate vascularisation of the transplanted bone block, which was integrated into the tissue of the recipient area. Bone resorption in the form of a thin fissure was observed in the external cortical layer, close to the alveolar crest of the block. Nevertheless, the growth in alveolar crest volume was deemed adequate for implant placement. A temporary crown was fixed immediately after placement because there was adequate stability, and alveolar crest defect was re-grafted with Cerabone and covered with Jason membrane before the flap was closed. After 4 months, an image was taken that showed bone augmentation and osseointegration around the implant. Conclusions: Preparing a jaw bone fragment as an allogenic bone block using an SLA model done successfully in GBR-type surgeries. The method allows block bone to be adapted for the recipient area, and is associated with significant time savings. Post-operative tomographic scans confirm augmentation of the alveolar ridge, making this a promising way for restoring aesthetics in the frontal area. -

ENAMEL MATRIX DERIVATIVE (EMD) IN ADVANCED INTRABONY DEFECTS—RADIOGRAPHIC BONE-FILL RESOLUTION AT 1-YEAR FOLLOW-UP

Objectives: This study aimed to evaluate radiographic bone fill of advanced intrabony defects 1 year after regenerative periodontal surgery with enamel matrix derivative (EMD). Methods: Ten intrabony defects were treated with scaling root planing (SRP) + MIST + EMD. Radiographic bone-fill was were compared at baseline and after 12 months. Results: Radiographic bone fill showed an enhanced mean number of pixels (p=0.0022). Conclusion: Intrabony defects can be treated successfully by regenerative strategies with EMD as shown by comparisons at baseline and after 12 months. -

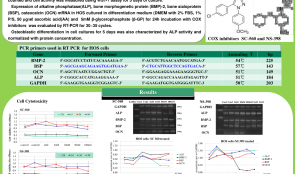

COX INHIBITORS SUPPRESS THE DIFFERENTIATION OF HUMAN OSTEOSARCOMA CELLS

Objectives: Recent reports of impaired bone healing associated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have raised major concerns. This study was aimed to evaluate the effect of COX inhibitors in osteoblastic differentiation of osteoblast-like human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells and to evaluate whether selective COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors have different effects on osteoblastic differentiation using HOS cells. Methods: HOS cells were cultured with selective COX-1 inhibitors (SC-560) and selective COX-2 inhibitors (NS-398). Cell numbers were counted and cell activity was measured using a WST-1 assay for 5 days of culture. Expression of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2, bone sialoprotein (BSP) and osteocalcin (OCN) mRNA was evaluated by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Osteoblastic differentiation in cell cultures was also characterised by ALP activity. Results: SC-560 and NS-398 treatment did not inhibit cell activity below the concentration of 50nM and 1μM, respectively. Gene expression of BMP-2, BSP and OCN was not changed when HOS cells were treated with SC-560, whereas ALP mRNA expression was decreased when treated with 50nM and 100nM SC-560. ALP, BMP-2 and BSP gene expression was not changed in the HOS cells treated with NS-398, whereas OCN gene expression was prominently decreased when treated with NS-398 above concentrations of 100nM. A decrease in ALP activity after 5 days of culture was observed in SC-560- and NS-398-treated cells. Conclusions: These results suggest that COX inhibitors at higher concentrations suppress the osteoblastic differentiation of HOS cells and downregulate osteoblast-related genes. The mechanism of action of selective COX-2 inhibitors also differs from that of COX-1 inhibitors. The long-term use of high-dose NSAIDs for the control of pain and inflammation after dental surgery could have a negative effect on bone healing and on the outcome of bone management. -

BONE AUGMENTATION WITH XENOGRAFT ASSOCIATED WITH BONE MARROW ASPIRATE CONCENTRATE (BMAC)

Objectives: To evaluate bony reconstruction of atrophic anterior maxilla using particulate grafts with or without autologous BMAC obtained via the BMAC method. Methods: Patients with atrophic anterior maxillae due to tooth loss (n = 8) were selected and split into groups according to the type of material used: the control group (n=4) received particulate xenograft only, the test group (n= 4) received a combination of particulate xenograft and bone marrow aspirate concentrate obtained via the BMAC method. Both groups received a collagen membrane to cover the xenograft. After 4 months, during implant placement, a bony sample was removed from the graft area using a trephine bur with a 2-mm internal diameter. The specimens were fixed and preserved for histomorphometric assessment of the following tissues: vital mineralised tissue (VMT), non-vital mineralised tissue (NVMT) and non-mineralised tissue (NMT). Cone-beam CT (CBCT) was performed three times to measure bony thickness: (i) prior to graft insertion, (ii) 4 months after grafting, and (iii) 8 months after grafting. The parameter used was local bone gain in millimetres. Results: Tomographic analysis revealed an increase in bony tissue in the CG of 3.78+1.35mm and 4.34+1.58mm at 4 months and 8 months, respectively. The TG showed an increase of 3.79+0.52mm and 4.09+1.33mm after 4 months and 8 months, respectively. Histomorphometric analysis revealed CG values for VMT, NMT and NVMT of 11.34±5.23%, 44.45±5.5% and 40.96±12.40%, respectively, and 64.31±9.12%, 32.41±10.38% and 0.73±0.56% for the TG. Conclusions: The use of a bone marrow aspirate concentrate obtained via BMAC increased bone formation in the graft area in the anterior maxilla. -

ECTOPIC IMPLANTATION OF HYDROXYAPATITE (HA) SCAFFOLD ASSOCIATED WITH BONE MARROW ASPIRATE CONCENTRATE OR OSTEODIFFERENTIATED BONE MARROW MESENCHYMAL STEM CELLS

Objectives: To evaluate the influence of bone marrow cells on bone formation in an ectopic subcutaneous model in mice. Methods: Six BALB/c mice were divided into three groups (n = 2 in each). In all groups, a xenograft was implanted subcutaneously. In the negative control group, the xenograft was hydrated with saline solution. In the positive control group, it was embedded with osteodifferentiated adult mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow. In the experimental group, the xenograft was embedded with bone marrow aspirate concentrate. After 4 weeks, the animals were sacrificed and prepared for histologic, histomorphometric and immunohistochemical analysis. The following tissues were evaluated: pre-osteoid tissue (POT), loose connective tissue (LCT) and remaining xenograft particles (XG). Results: There was statistically significant difference (p=0.008) in POT area between the negative control group (0+0%) and the other two groups (42+11% experimental; 56+55% positive control). Similarly, there was a statistically significant difference (p=0.006) in LCT area between the negative control group (49+18%) and the other two (3+9% experimental; 0+0% positive control). There were no statistically significant differences between all three groups for XG area (p=0.143). Conclusions:The use of a mineralised scaffold loaded with either concentrated bone marrow aspirate or with osteogenically-induced bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells favours the formation of osteoid tissue compared to scaffold alone.